Chlamydotis macqueenii

The Asian Houbara is one of 26 species of a family of birds called bustards, which are characterised by long legs with only 3 toes, highly adapted for life in open landscapes. Many bustard species are globally threatened, including the Asian Houbara (categorised as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List).

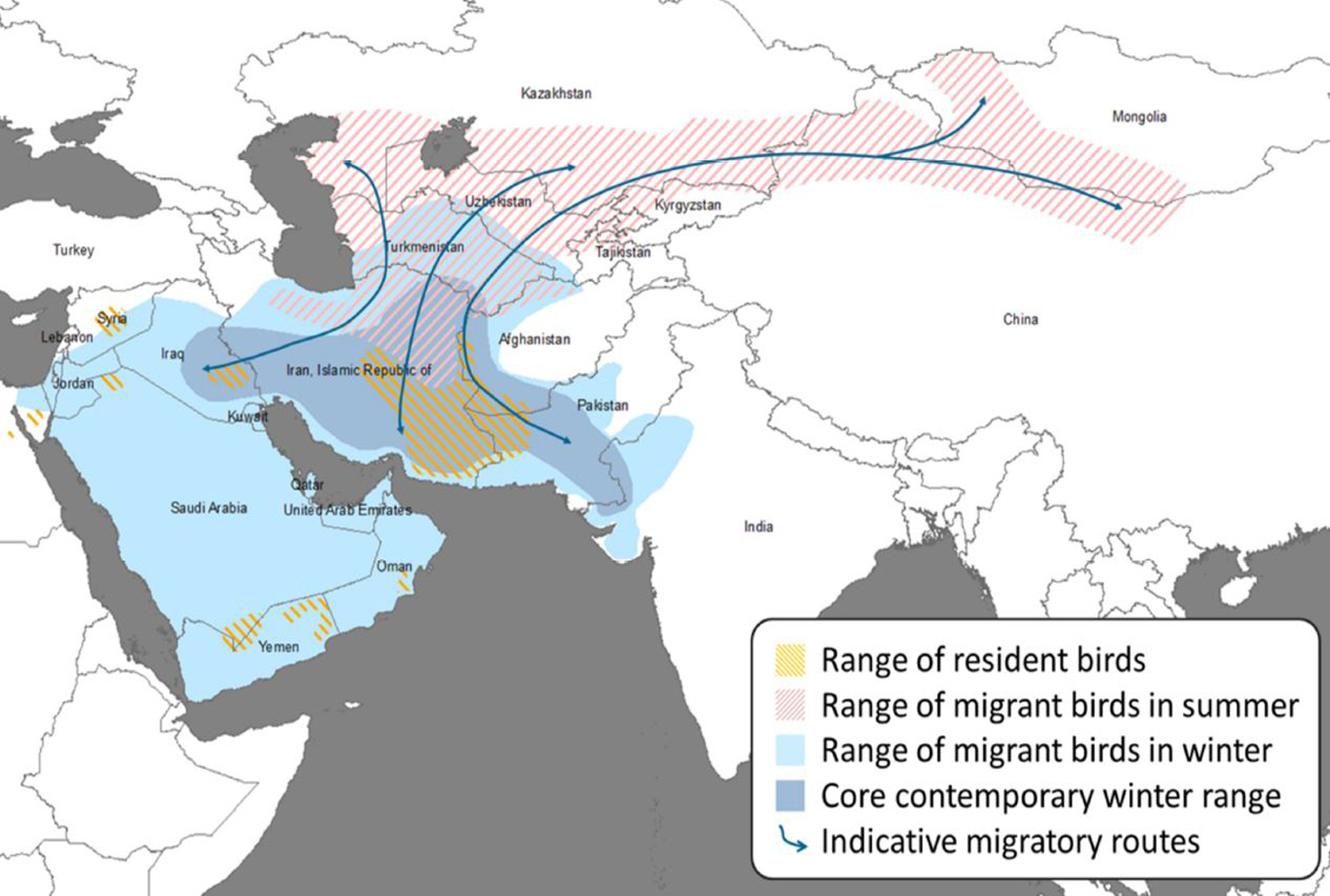

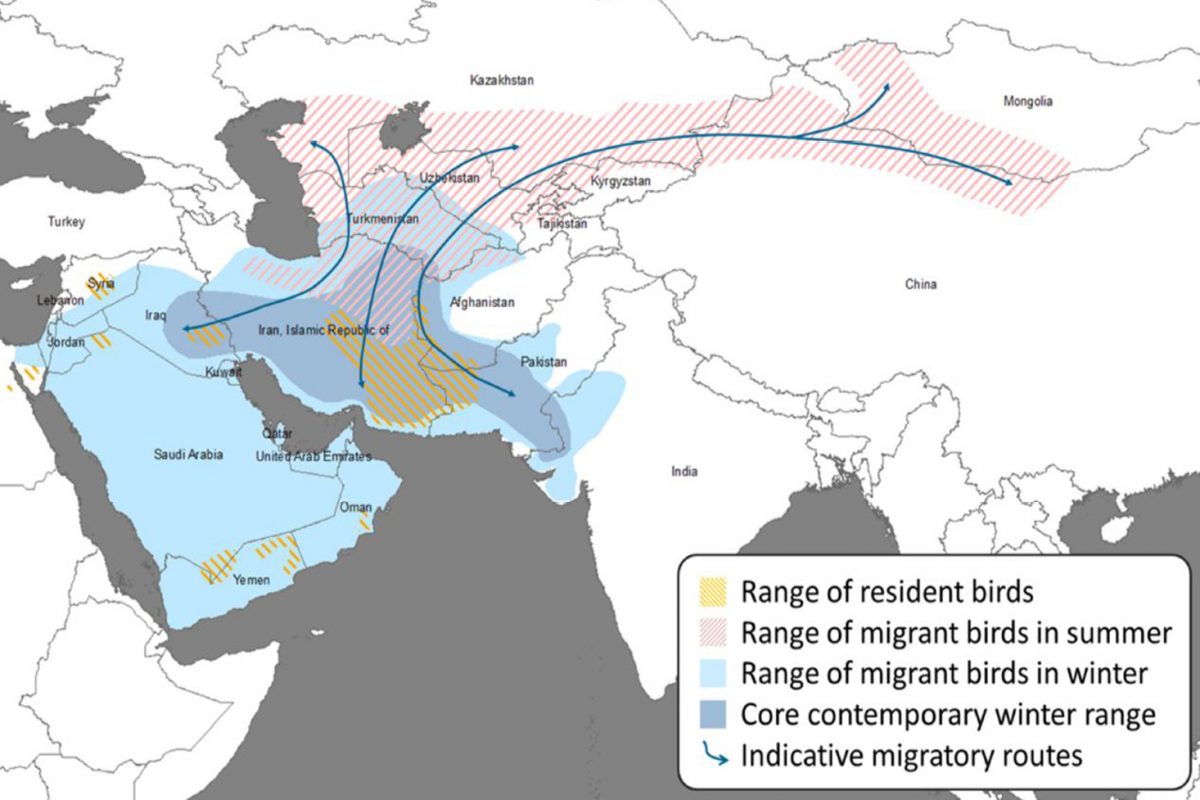

Asian Houbara occur from the Arabian Peninsula through Central Asia to China. The central and eastern populations are migratory, wintering in western south Asia and the Middle East. The range of resident birds in the Arabian Peninsula was formerly much larger, and the core wintering area once extended down the west side of the Arabian Gulf, but overhunting and other factors have caused changes that only time and careful management of populations can reverse.

Asian Houbaras are birds of arid landscapes commonly described as ‘semi-desert’ and ‘desert edge’—sandy grasslands and semi-arid shrublands, salt pans and stony plains dotted with shrubs. Such habitats vary subtly but distinctly, and houbaras live at different densities in them, as our research has shown. Outside the breeding season the birds are often tempted to visit cultivated areas fringing these natural habitats, where nutritious crops such as alfalfa provide green vegetation and insect prey.

Asian Houbara are perfectly camouflaged to blend into the desert landscape. This gives them great protection against predators and adds to the challenges that hunters must rise to, but it also makes studying some aspects of their lives very difficult. In our research we must count displaying males from a distance using telescopes in order to estimate the numbers and densities of birds in particular areas—the females are almost impossible to see.

They eat insects of many kinds varying with season and circumstances (in late summer in Uzbekistan mainly ants and beetles), and will take small reptiles or even young birds when they can. They also eat green parts of plants, often in large amounts, including a wide range of desert shrubs but also alfalfa and other cultivated legumes. They are able to survive entirely without water and to find food when the desert appears empty of life and nothing edible is obvious to the human eye. The contrast between the size of the birds and the apparent lack of food at certain times of year emphasises that houbara are highly adapted to cope with large changes in food availability.

Asian Houbara is a lekking species. Every spring the males perform a spectacular display in the breeding areas, running with their heads half-hidden in their breast feathers, trying to attract and mate with as many females as possible. The display can be visible from far across the desert, and females are thought to choose the best males to father their offspring. After mating, the male plays no further part in the nesting process.

Female Asian Houbara lay up to 5 eggs in a nest on the ground and incubate them for 22 or 23 days. They use their camouflage and the isolation of the desert as their first defence against nest predators. Our research shows that they make very careful choices over where they lay their eggs, selecting places where the vegetation is tall enough to conceal them from potential predators but short enough to let them use their long necks to scan the horizon for danger. Approximately half of clutches survive to hatching.

Houbara chicks form a bond with their mother even while they are still in the egg, using calls to communicate. They leave the nest with their mother soon after hatching. At first they are rather clumsy and slow, needing exercise to build their strength, but with each passing day they can walk longer and longer distances. They peck at potential food sources as soon as they can stand, but the mother calls them to food items when she finds them. At 5 weeks their wings have grown enough to let them fly short distances, but the mother cares for them until they are independent at around 2 months old.

Despite their large size (with males a little bigger than females), houbara are fairly light in weight, and fly strongly. On migration they can cover many hundreds of kilometres in a few days, travelling at steady speeds mainly by night. When hunted, they prove to be impressively fast and agile (‘rashiq’ ) birds.

As in all animals, Asian Houbara suffer the highest rate of mortality in the first year of life. Once they are adult, they are capable of living much longer than a decade, having few natural enemies capable of killing them. Houbara were hunted with falcons for food for centuries in Arabia, but since the availability of off-road vehicles and expansion of hunting, mortality rates now exceed breeding rates.

Unregulated hunting with falcons or firearms, illegal trapping for the training of falcons in the Gulf, and habitat degradation have together led to declines throughout the range of the Asian Houbara, causing it to be categorised as ‘Vulnerable’ to extinction on the IUCN Red List. These three threats are focused in the wintering areas, from central Asia south to Pakistan, but affect all migratory and resident populations. Our research in Uzbekistan reveals that the breeding population there may be declining by 9.4% per year. Now these threats are compounded by a new risk from powerlines, as our research has shown. There are even possible dangers from captive breeding, the key measure being used to save the species.